A musician slips away...

The life of Peter Forrest, AKA Peter Fluid of 24-7 Spyz, came to an abrupt and horrific end that's left his peers shaken. A look back at the work he left behind.

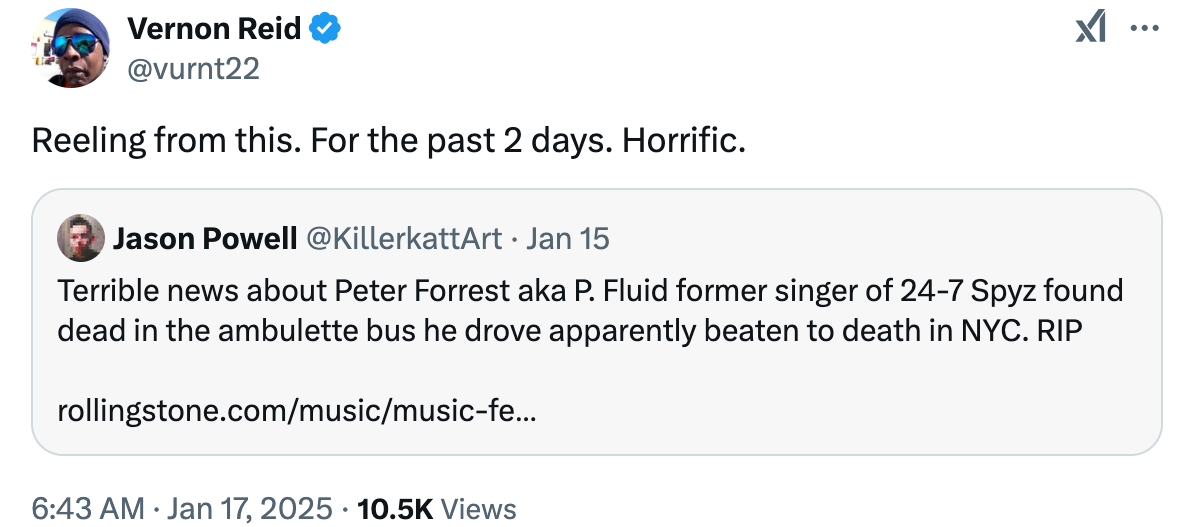

On the morning of January 13th, just over a week ago as I write this, a 64-year old ambulette driver was found dead in the back of his work vehicle at the end of a quiet residential street in The Bronx. According to multiple reports, the man was discovered lying face-down in a pool of blood with “extensive trauma to his body”—wounds apparently incurred from having been beaten to death. Although a suspect has since been arrested and charged with murder, the circumstances and motive remain unclear.1

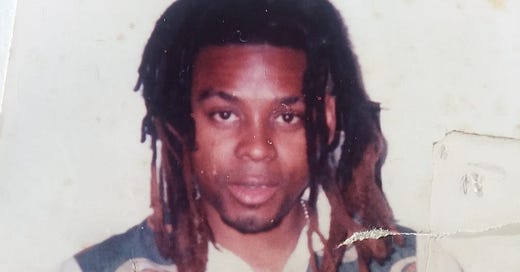

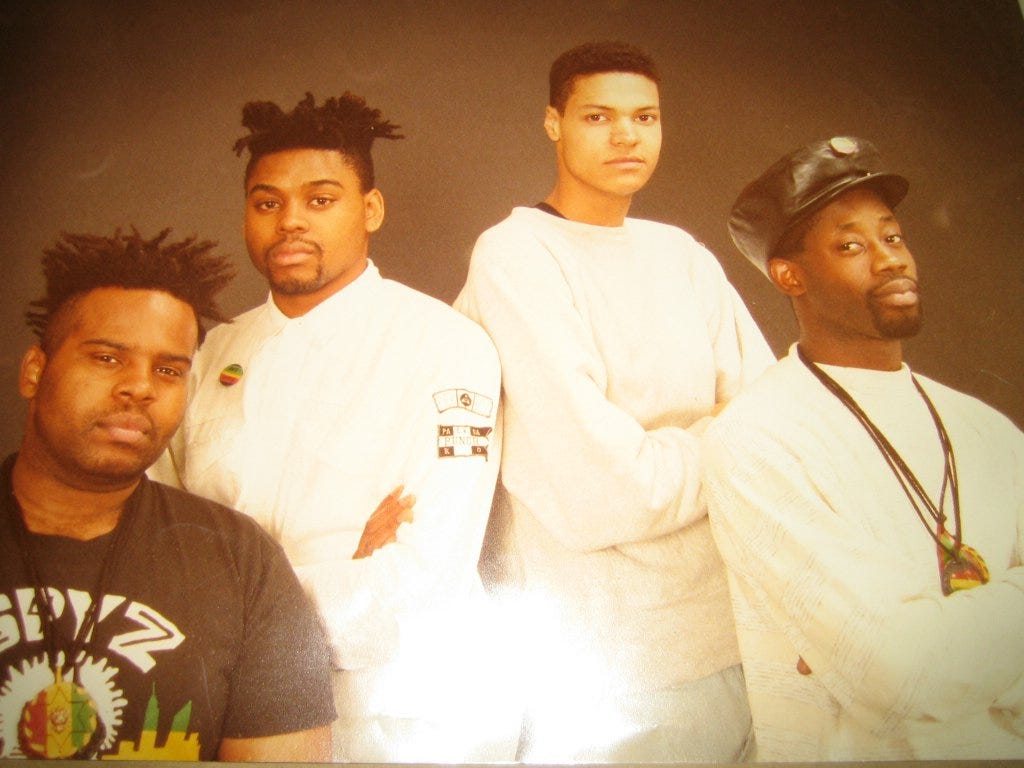

As New York City news outlets began to circle back with updates, it soon surfaced that the victim was musician Peter Forrest, best known as Peter Fluid, one-time frontman of the Bronx-based multi-genre group 24-7 Spyz. The band, which Forrest co-founded with guitarist Jimi Hazel in 1986, helped usher-in an era of unprecedented stylistic freedom alongside acts like Fishbone, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Living Colour, Murphy’s Law, Urban Dance Squad, and De La Soul.

The late singer, songwriter, and U.S. Army veteran fronted 24-Spyz under the moniker P. Fluid (get it?) until his abrupt departure in late 1990, singing on two pivotal albums, 1989’s Harder Than You and 1990’s Gumbo Millennium. He returned for 1995’s Temporarily Disconnected, only to leave the group again for good that same year. The first two Spyz albums, however, positioned the band in the thick of the musical uprising that shook the world by storm as the ‘80s gave way to the ‘90s.

If you were around at the time, you’ll remember that what we commonly refer to as “alternative music” today actually consisted of multiple branches on a rather tangled tree. Like many of their contemporaries, 24-7 Spyz found their footing on a number of those branches. In 1990, for example, they took Primus out as an opening act on a jaunt headlining U.S. clubs.

This was at a point when both bands were viewed as the face of the nascent “funk-metal” movement that saw audacious, slapping bass players in the spotlight more than ever before. Several other acts connected to that movement—including Faith No More, Suicidal Tendencies/Infectious Grooves, Mindfunk, Death Angel, etc—either had roots in other sub-genres or would later be categorized under the broader “alternative” umbrella.

On a personal note: the 24-7 Spyz/Primus bill banged and clanged its way through Rochester, NY on August 31st, 1990—only my third day in town after my mom and brother dropped me off to attend my freshman year of college. I was still in the campus-orientation phase, so I didn’t know my way around yet. Concerned that I’d get stranded with no way back to campus, I opted not to go.

To this day, I regret missing that show—although, strangely enough, it still occupies a special place as a kind of gateway marker to the beginning of my life away from home. It’s actually rather fitting that I missed it, as there are so many decisions from that period that I look back on with a wistfulness so potent it nearly doubles me over, though I do find comfort in my amusement at the trainwreck-in-the-making my story was about to become.

In any case, though 24-7 Spyz only minimally touched on rap stylings, the fact that they grew up in the South Bronx meant that they were inevitably steeped in a hip hop sense of style. Hazel and longtime bassist Rick Skatore, in fact, both hail from a neighborhood that’s very close to where I lived and attended elementary school as a child. I was in high school when Harder Than You dropped, and I can tell you first-hand that there was something thrilling—and deliciously confounding—about a band that dressed like the love children of rappers and skate punks who didn’t rap but instead peeled your face off with such a blistering attack.

Even in an atmosphere that nurtured eclecticism, however, 24-7 Spyz staked out their own ground by embracing both metal and classic soul more unabashedly than anyone else had up to that point. When the Spyz first started making waves on a national scale in 1989, Fishbone and Living Colour were already being hailed—and interrogated, challenged, and doubted—as avatars of the idea that, yes, there were black musicians with an affinity for rock music, and heavy rock at that. Much like those two bands, the Spyz wore their omnivorous tastes on their sleeve.

But, where Living Colour and Fishbone both exuded an air of musical sophistication, 24-7 Spyz dove head-first into genre like a bunch of stoned, giggling college kids buffet-hopping between ten different types of cuisine. Moreover, though Fishbone and Living Colour were certainly capable of putting the pedal to the metal when they chose to, the Spyz were the only band of the three who could truly keep pace with the unbridled speed and aggression of groups like Nuclear Assault, Agnostic Front, Sick Of It All, and Ludichrist. It’s not for nothing, after all, that New York’s hardcore/crossover underground was the first scene to embrace them.

Yes, it’s true that Bad Brains had been instrumental in creating the hardcore punk template that pretty much all of their successors drew from, even iconic ground-floor participants like Ian MacKaye and Henry Rollins. They had also, by all accounts, established themselves as one of the most ferocious live bands in the history of American music a full decade before Harder Than You. But Bad Brains, believe it or not, had initially set out to play an amped-up permutation of jazz fusion. The north star that guided Hazel, Forrest, and their Spyz bandmates came in the form of The Isley Brothers, Rufus, and Motown.

Of course, there were heavy traces of Jimi Hendrix and Funkadelic in the recipe as well. Hazel was christened with the moniker “Jimi Hazel” by an older musician who’d observed the influence of Hendrix and Eddie Hazel on the then-fledgling guitarist’s playing. (His real name is Wayne Richardson!) Still, if you didn’t know better, you could easily mistake the Spyz’ thrashed-up remake of Kool & the Gang’s “Jungle Boogie” for the work of the Chili Peppers, Scatterbrain, or Suicidal Tendencies. Which is to say: you really had to strain to hear the soul in there.2

For all his dexterity and inventiveness with cymbal patterns, drummer Anthony Johnson’s helicopter-like footwork didn’t exactly swing much—at least not when the band blasted away at full bore. Credit where due: Johnson’s sense of feel was much more apparent when he played ska-based rhythms, and you can really hear his maturity and finesse on Temporarily Disconnected. Further, his playing on the first two records was hardly served by an overly round snare sound that plops down in the mix like a giant elephant’s backside.

To be fair: many, many recordings from the period suffer from this same issue, but it’s also fair to point out that drummers like Fishbone’s Phillip “Fish” Fishman and Earl Hudson of Bad Brains positively oozed with swing, even at the breakneck tempos that became the Spyz’ bread and butter. Meanwhile, Skatore favored such a slap-happy style back then that you’re not going to hear the subtlety and grace of touch that made the lines of soul titans like James Jamerson, Larry Graham, and Nathan Watts so breathtaking.

By the same token, 24-7 Spyz’ balls-to-the-wall approach is part of what made them special in the first place—especially onstage, where their confetti-bomb energy was perhaps best suited. And if the gang-style vocals sound especially dated and naive today, the music still courses with the spirit of an era rife with artistic adventure, where it felt like new musical combinations were constantly spinning into existence from every conceivable direction (and bouncing off of one another to boot).

When you listen to 24-7 Spyz now, it’s important to remember that they were the product of an especially exuberant time in music, where execution was often overlooked in favor of energy and intention. Look hard enough past the cacophony and chaos, then, and you’ll find the soulfulness somewhere in there: certainly in Hazel’s colorful, unorthodox chord voicings, which Chicago Tribune music critic (and my primary influence) Greg Kot described as “the fluidity of Wes Montgomery [blended] with flamethrower riffs worthy of Eddie Van Halen” in a four-star review of Gumbo Millennium.

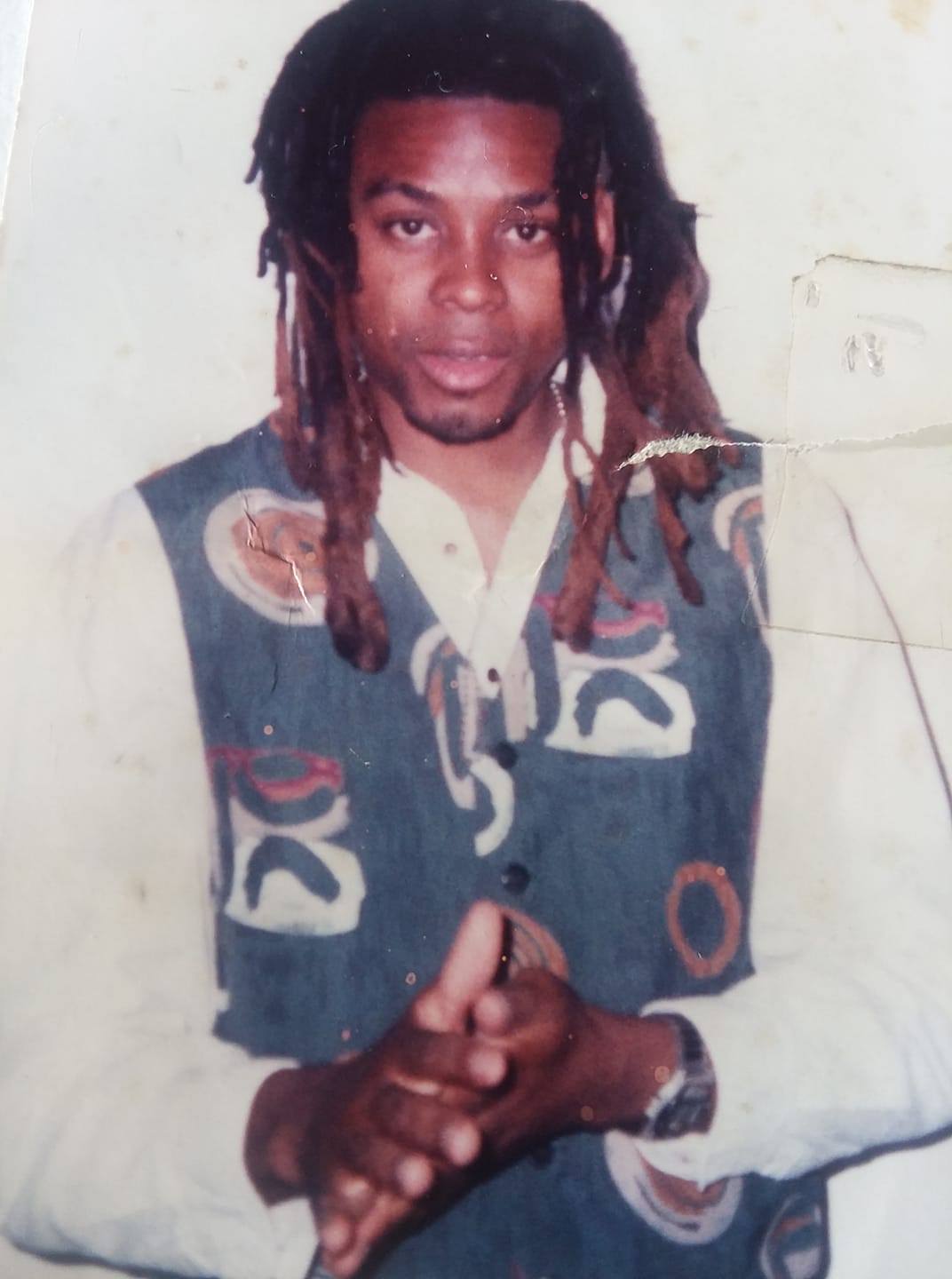

Perhaps above all, though, you’ll find the soul in Forrest’s voice. Like his bandmates, Forrest was certainly fond of pushing the envelope musically. And, much like his predecessors HR from Bad Brains and Living Colour’s Corey Glover, Forrest’s penchant for screaming his head off belied the breadth of his range. In 24-Spyz’ heyday, he was able to convey a great deal of emotion even while scraping the back of his vocal cords to produce ear-piercing shrieks. And when he stopped to take a breath and sing, the impact was undeniable…

For me, the saddest detail in the New York Times’ account of Forrest’s death—aside from the fact that he was killed in such a gruesome, seemingly senseless manner—is a quote from a neighbor who lived in his building off Pelham Parkway in The Bronx. According to the Times, the other tenants had no inkling of Forrest’s erstwile brush with fame all those years ago. One of the neighbors, however, was at least aware that Forrest made music: “Sometimes,” the neighbor told the Times, “you could hear him playing guitar faintly. You could tell he knew his stuff.”

On reading that, I was struck by the image of a musician sitting alone in their apartment, the sound of unaccompanied guitar resonating softly through the walls. The first thought that bubbled up after My god, how tragic was one that nags at me often: What happens to all those ideas a person never gets around to finishing? Also: How do we properly honor a life’s worth of creativity—particularly the work that hasn’t reached an audience?

I wondered what musical goals Forrest had been looking forward to when he woke up on the day he died. And I wondered what remnants of his ideas were left in his living space. Surely, there were notebooks, tapes, audio files on a computer or a phone, maybe fliers and mementos from what must, to someone in their mid-sixties, have felt like a lifetime ago…

Unbeknownst, most likely, to the majority of his fans, Forrest co-wrote a novel, too: a Hasidic horror story—yes, you read that correctly—set in Brooklyn’s “ultra-Orthodox” Crown Heights neighborhood that garnered a 2013 write-up in the Jewish magazine Tablet. The genesis of the book, titled The HarlequinX, is so remarkable and outlandish that it’s hard to tell whether Forrest had followed his muse to a creative masterstroke, or to a realm so zany it would’ve made Mel Brooks proud. (You must do yourself a favor and read the Tablet piece. Kudos to Forrest for daring to write about such an insular community from an outsider’s perspective, and also for ingratiating himself with community leaders along the way, which the article covers.)

By the sounds of it, Forrest had ventured into that creative zone where the line between inspiration and lunacy blurs so much that it’s impossible to tell the difference—or even to discern why the difference matters at all. One thing is clear, though: in the latter-day stages of his career—and, indeed, his life—Forrest was unquestionably marching to the beat of his own drummer. So much so, in fact, that the enigmatic goth/cabaret/Guignol persona he’d cultivated with his horror-themed group BlkVampires is hard to square with the socially-conscious spark plug last seen 30 years ago diving into crowds and pinballing across stages like a fleet-footed linebacker.

Of course, it’s possible that Forrest had been harboring multiple facets of creativity all along. And, in retrospect, the Screamin’ Jay Hawkins-esque presentation he adopted post-Spyz under the stage handle Forrest P Thinner (eventually shortened to Forrest Thinner) does share some traits with the theatrical rasp we hear in his work with the Spyz. (The similarities were a lot more apparent in the BlkVampires live show.) Not to mention that he released a single titled “Eric Garner” in 2015, a clear indicator that he wasn’t done addressing topical subjects.

A handful of posts from Forrest’s Instagram page—such as this one from Donald Trump’s 2024 campaign rally in the Bronx, or this one comparing Kamala Harris to bird shit—would seem to indicate that he supported Trump. Sometimes, however, like in this re-post of a meme depicting Trump as a King Kong-like gorilla, it’s not so clear. Evidently, Forrest preferred leaving cryptic breadcrumbs for his followers to make sense of.

His posts were frequently hilarious, though. And, not unlike the various guises he assumed with his singing voice, he could shift from, say, from oddball to touching without skipping a beat. About a week before Christmas, for example, Forrest posted an extraterrestrial interrogation meme in response to the mysterious drone sightings over New Jersey. Days later, he re-posted Nat King Cole’s “Merry Christmas” with the hashtags #Christmas #holidays #love #family #friends—and, of course, #blkvampiresx!

Combing through the various quips and jabs that I had to stop and think to understand—if I understood them at all—I found myself thinking that it was a shame Forrest didn’t post more. What would he have done, I wonder, if he’d established a broader reach? Because, at least in terms of having his own distinct way of observing and outputting, it appears as if he’d have been well suited for life as an online personality. And one can only imagine the witty banter he’d have gotten into with an engaged following.

That said, Forrest revealed very little about his actual personality. He posted sporadically, with no apparent rhyme, reason, or rhythm to how often he chose to do it. He also sometimes super-imposes the BlkVampires web address onto memes and photos that had nothing to do with his music, a head-scratching move that leads me to wonder whether he was somewhat lost in his sense of how to promote his work—or whether this was merely a sign of the same rebellious humor we’ve seen from any musician who’s ever slapped their band’s sticker in inappropriate because it’s fun to raise eyebrows.

Looking back, you get the sense that Forrest was communicating to the world while keeping hidden behind a protective barrier of funny memes. Shades of that old familiar flamboyance shine through, but it’s impossible to gauge who he was at age 64, much less how he’d evolved from a 20 year-old Peter Forrest serving in the U.S. Army to P. Fluid to Forrest P Thinner. He didn’t quite leave enough behind for us to connect the dots. He was slightly more disclosing on his personal Facebook page, but not much.

There are, of course, clues in the music. Ever since hearing the Spyz song “Dude U Knew” back in 1990, I’ve been haunted by the lyric I’m just like you / afraid to bleed. To whatever extent Forrest was or wasn’t singing from his own experience on that song, he breathed an aching, lifelike vulnerability into them that rings ever more powerfully now. More recently, we can look to the BlkVampires song “My Own Father,” where he sings Sometimes I seek my own father / I keep looking for a hero / a person I should admire. Surely, his fans will pore through all these songs and hear them differently now—as they should.

For whatever it’s worth, the music Forrest made after his departure from 24-7 Spyz barely registered with the public. Other than the Tablet piece, a blurb-length concert review in The Source (“the bible of hip hop”), an artfully written EP review3 in the legendary horror magazine Fangoria, and a handful of blog posts (like this one from 2012), Forrest left a pretty meager footprint in the music press. For Rolling Stone’s obit, contributor David Browne had to reach all the way back to a 2018 interview from horroraddicts.net to dig up a quote from Forrest. (Forrest did appear as a plaintiff on The People’s Court sometime after 2015, but he wasn’t in character, so it didn’t serve to promote his music. If any BlkVampires fans watched at the time, they probably wouldn’t have recognized him.)

What jumped out to me right away on browsing his links was how under-developed his promotional infrastructure was. Forrest was still using the long-outdated platform Sonicbids, for example, to plug his artistic endeavors. And, according to the shows he listed on the page, he’d only played a smattering of dates around New York City between 2014 and 2019. Since 2019, he’d released just two singles, both in 2022. Essentially, he’d spent the last three decades toiling in obscurity, but one wonders what led him down this path.

Other than the musicians he’d enlisted to play with him, it doesn’t appear as if there was much, if any, by way of a manager, booking agent, publicist, or producer behind his efforts. “He always kept that same intensity toward his music,” longtime collaborator and BlkVampires bandmate Ray Anderson told the Times. “It was his goal to reach the level he’d reached with Spyz. So he never lost that ambition, that drive. He always wanted to get back on top.” If that’s true, it’s hard to hard to fathom how he thought he was going to get there.

To think that Forrest may have spent the rest of his post-Spyz life pining for another taste of the limelight adds an extra layer of poignance to the tragedy, but I have my doubts. For one—and this is the second that thing that jumped out at me—Forrest kept his face almost entirely concealed throughout his photos and videos, if he even appeared in them at all. Again, he did post some pics of himself on his personal Facebook, but in an age where public figures—musicians especially—relentlessly document themselves with a thirst for attention that verges on narcissism, Forrest’s approach stands out precisely because it he didn’t try to stand out!

Likewise, with the release of the singles in ‘22, he inexplicably re-branded BlkVampires as BlkVampiresX, ditching what little equity he’d built up with the bandname up to that point while also binding himself to the original name, only this time with a more impractical spelling. On his Sonicbids profile, Forrest admitted that “there may be blurry lines” between the two projects, but then billed BlkVampiresX as “his first-ever solo project.”

But the third thing that jumped out at me was how much power was still left in that voice. Pressing play on a BlkVampires release for the first time, I was quite taken aback, like a strong gust had come in through the window and nearly knocked me over. Because there it was: that signature howl that could soar and dive, that could be sweet and sly, earnest and seductive, deep and piercing, wide and pointed, sensitive and fiery, ethereal and anguished, vulnerable and aloof, convivial and impenetrable, that voice that transports you from a church choir to the filthy bathroom at CBGB, and from the most high-minded ruminations on life, love, and injustice to the everyday rat race… there it was, all in the same voice somehow.

Forrest may have named himself P. Fluid as a silly, grade school-level dick joke, but fluid was a more perfect descriptor than maybe even he had dared to imagine. Yes, there it was again: that voice that had so perfectly faced frontwards for the caterwaul of a band whose every member kept their vigor turned all the way up the entire time. However we might assess the impact of Forrest’s efforts on his own, let it first be noted that he still had the goods. The charisma was still apparent too—even if he had become something of a recluse (albeit a recluse who still performed).

Over a ten-year stretch from 2005 to 2015, BlkVampires put out just under 30 songs—one full-length album, two fairly long EPs, and the aforementioned “Eric Garner” single. It’s not the most prolific streak ever, but it’s not nothing either. Admittedly, there’s a roughness to the production values. None of the material sounds quite fully realized, and it’s obvious that Forrest could have benefited mightily from both an attentive producer and a capable mastering engineer to give the songs the roundness they would have needed to meet professional standards.

For whatever reason, Forrest never managed to give his music proper polish. On the Spotify playback, even the spacing between songs lacks precision. When you press play, in spots there’s far too much dead air until the music starts. Listening back, I was reminded of the glut of cd-r’s onto which inexperienced bands burned their own music by the hundreds during the early 2000s. Even so, the recordings are certainly not without their charm.

Warts and all, Forrest’s body of work abounds with the appeal of an outsider artist who’d committed to his warped—even captivating—vision. Although his band appears to have been quite well-rehearsed, he could have leaned into lo-fi production techniques to enhance what he was trying to get across. And on hearing his tunes (even moreso on watching them performed live), I have to presume that Forrest still had more songs to bring into existence. Of course, I can’t help but wonder how many of his ideas never saw the light of day.

One point of order, though: The back half of the BlkVampires self-titled full-length consists of songs that appeared in more completed form on the Spyz album Temporarily Disconnected. From the sounds of it, either Forrest made demos of the material on his own that later became the primary blueprint for the Spyz release, or he took rough mixes home from the Spyz sessions and passed them off as his own work. Having compared the two sets of recordings, I’m heavily inclined to believe the latter. If Forrest put those tracks together on his own, that would mean the rest of the Spyz mostly didn’t play on the songs he brought in for that record, which seems way too unlikely to me.

Any which way, those demos offer some clues as to the source of the friction that broke the Spyz up not once but twice. On his Sonicbids page, Forrest describes himself as “the main force behind the band 24-7 Spyz,” a claim that, on first glance at least, reeks of lead singer’s disease. So does the Temporarily Disconnected credit that reads “All songs written by P. Fluid, except for where noted.” Because, in this case, ”except where noted” means half the songs!

These signs seem to point to a struggle over a sense of ownership over the music—nothing, of course, that we haven’t seen before in countless other bands. But this one is particularly difficult to decipher, particularly now that Forrest isn’t here to make his case. What we’re left to deduce, however, is that Forrest either made musical contributions he didn’t feel he got enough recognition for, or he had an inflated sense of his contributions. It’s also possible—even likely—that both are true to some extent. After all, multiple truths can exist simultaneously within the ultra-dysfunctional matrix of a band relationship.

In a lengthy interview that Hazel gave to Steven Payne of the Bronx Historical Society in February of 2024—just under a year before Forrest's murder—Hazel recounts in depth how Forrest quit 24-7 Spyz just as the band’s momentum was cresting, announcing his departure onstage on the final date of their run as the opener on for a stretch of Jane’s Addiction’s historic campaign supporting their era-defining 1990 classic Ritual de lo Habitual (which, not incidentally, happens to be my favorite album ever made). Hazel explains that he and Skatore were completely blindsided.

Clearly, 24-7 Spyz were on an upward trajectory, and Forrest appears to have been responsible for derailing it, at least according to Hazel’s telling. Out of the three hours and seventeen minutes that Hazel speaks to Payne, he spends the last forty minutes unpacking the dynamics that led to the unraveling of his relationship with Forrest. After quitting the second time, he and Hazel never spoke again. Naturally, Hazel is much warmer in his recollection of the band's origins and ascent, and one imagines that he feels haunted by his words today, even if they still ring true just as true for him.

It goes without saying that the finality of a person's passing tends to soften the heart and nullify grudges. Posting on Facebook, Hazel wrote with both candor and tenderness about his long-estranged former bandmate’s passing. And from the sounds of it, it wouldn’t have taken someone dying for Hazel to be open to reconciling: “He'd mentioned to [a mutual friend] not long ago that he wanted to speak to me,” Hazel’s post reads. “If he’d called, I would've answered. I have no idea what might've come from it, but I have a deep-rooted feeling that the long overdue conversation we should've had would've been a beautiful thing.”

There’s much more to the post, but it ends with a plea from Hazel, who lost his own father just days before Forrest’s passing: “Please know that tomorrow isn't promised to ANY of us. If you need to make a long-overdue phone call to begin the process of making things right with someone, PLEASE DO IT TODAY!!!!!”

Powerful words indeed. May they serve as a lesson to all of us. The only thing I’d add is: If you’re a creative person, I’d urge you to picture what would happen to your ideas if you should happen to pass away, difficult as that may be to ponder, and to make an effort to archive your work and works-in-progress so that others close to you might be able to sift through them and, if appropriate, share them after you’re gone. You can at least try to ensure that your life’s worth of expression doesn’t get lost in a vacuum.

Maybe artists should leave a kind of “will and testament” with instructions for how both their finished and unfinished work should be handled. Because, after all, what good are the things we’ve made if they have to “die”—sit there silent, unseen, and unspoken-for—when we die?

NOTE: Sharing Jimi Hazel’s 2024 interview here might seem inappropriate, like digging for gossip at a wake, but I include it here because it's illuminating on a number of levels. Imagine going to the funeral of an uncle you've long known to be estranged from another one of your uncles, where both uncles once owned a deli that you spent some joyful summers working at as a teenager. You certainly wouldn't bring up their old gripes in front of your family members at the height of their grief, but it's not like you'd forget about their estrangement either—nor could you fault yourself for sitting there thinking about it the whole time and wanting more clarity on the situation, since their estrangement intertwined with your own cherished memories.

That’s kinda how I feel about what it’s like to be a fan of a band. These are, after all, real people whose real lives we end up getting attached to in this oddly indirect and somewhat intrusive—yet mutually inter-dependent—way. There certainly is a line where curiosity crosses over into ownership and poor taste, but relationships in bands are extremely complex. When writing about them, I do my best to be as mindful as possible. For the people who love the music that Jimi Hazel and Peter Forrest made, my intention here is to honor in equal measure the music itself, the fans’ feelings about the music, and the humanity of the people who made the music.

Much love…

<3 SRK

According to a NY Daily News report from January 19th, “investigators are working on the theory that Forrest caught [suspect Sharief] Bodden breaking into the ambulette, and believe Bodden then in a rage pummeled Forrest to death and placed his bloodied body in the back of the ambulette before ditching the ride, law enforcement sources said.” If true, that rules out the possibility that Forrest and Bodden had some kind of previous connection that might could have played into the motive for the crime.

You can definitely hear shades of classic R&B after the first two albums: on post-Forrest tracks like “Earth & Sky” and “Sireality”, as well tunes Forrest did sing on like “Why” and “Choose Me”, both from Temporarily Disconnected.

I didn’t find the Fangoria review online, so I copied it from Forrest’s Sonicbids page:

Watching horror spread its spindly tendrils into all realms of pop culture is always a pleasure, especially when it works. That’s why NYC band blkVampires are so notable. Formed three years ago by frontman Forrest Thinner, the band blends Goth industrial, deep soul and metal together in a mad cocktail of macabre music that is akin to Sam Cooke meets Screamin’ Jay Hawkins by way of Fishbone, with more than a dash of Coffin Joe Grand Guignol tossed in for good measure.

“Horror movies are my shit,” says the energetic Thinner. “And to me, that’s what makes blkVampires hot. It’s the element that makes people gasp. When I see a horror film, I look to see who did the score, because even if you’re blind, you should always be able to feel a good horror movie. Just hearing it should make you jump; sometimes that’s even more effective than seeing it.”

Onstage, the band is like a scaled-down Parliament, with the mad musicians hammering away on all manner of instruments while the top-hat-wearing, ghoul-faced Thinner holds court like a Flava Flav by way of Barnabas Collins. The music rocks hard, and the demented visual aesthetic (not to mention Thinner’s bizarre lyrics) tie up their sonics with creepy bravado. Their new five-track EP The Devil’s Music is as good as rock ’n’ roll gets.

“The Devil’s Music has everything,” Thinner says, “from jack-in-the-boxes to witch cackles, laser beams, jailbird inmate screams, boxing-ring bells and growls, all slammed into the mix along with an incredible guitar balance of shredder leads, Cap’n Crunch power chords and soulful rhythms and leads. The drums and bass are fiercely sick with their rhythm and awkward timing, the samples sabotage the atmosphere entirely and the vocal range is all over the place. It’s like a monster just found out what melody is.”

—Chris Alexander