The usual suspects are at it again — tripping over themselves to convince us that Taylor Swift’s worldbeating domination of the pop universe needs to be understood in Culturally Significant terms.

That’s what’s I thought, anyway, on watching YouTuber Rick Beato’s new video in response to The New York Times Magazine’s cover story, titled How Big Is Taylor Swift? To my surprise, author Joe Coscarelli’s commentary is not only thorough but refreshingly fair (more or less). Sure, as Beato points out, the framing of Swift’s career accomplishments against those of The Beatles, Michael Jackson, Madonna, Britney Spears, Beyoncé, and Drake is slightly mis-leading, even as Coscarelli makes his case based on hard numbers.

That aside, though, what struck me is the article’s sober tone (not to mention the online version’s visually stunning layout, with its wealth of graphics and tables, the kind you’d find at museum exhibits where you get to push a bunch of buttons and watch factoids come to life on a screen). Coscarelli does his utmost best to remain objective, and succeeds well enough that one can decide whether to take or leave his bias, which remains subtle throughout the piece. (I wasn’t actually surprised at the elegance of Coscarelli’s writing, by the way. I’ve recoiled at The New York Times since I was in middle school, but the Magazine’s writing routinely floors me. Go figure.)

The fact that a Times contributor would address Swift with anything more toned-down than gushing enthusiasm has me wondering if a change is in the air. Are the cognoscenti turning on Taylor Swift? And is she about to find herself being ushered out of relevance? If critics did start to sour on her, could they succeed in shaping public perception — or succeed enough to put a dent in the sheer enormity of her success? How will we remember Swift in the future, whenever her star does inevitably fade?

Elsewhere, Utkarsh Mohan, the Singapore-based host of the YouTube channel Ministry of Guitar, offered a rather measured and thought-provoking response to Coscarelli’s article, proposing that analytics-driven marketing is moving us towards a creative landscape devoid of the human factor that makes art strike a chord with people in the first place. Mohan’s delivery is less hyperbolic than I’m making it sound, and I would urge you to watch his breakdown of the idea that there’s a diminishing return in optimizing musical characteristics simply because they’ve succeeded on a mass scale in the past.

Both Mohan and Beato argue that Swift is fundamentally a product — a marketing entity, not a creative one. I wholeheartedly agree, and they manage to put their finger on what irks me so much about the feverish mania surrounding her. Inevitably, there will be predictable cries dismissing Beato as an “old man yelling at cloud” figure, but let’s not forget that The Beatles (and other legacy artists like them) are still moving the needle in today’s pop-culture ecosystem.

Not to mention that Mohan is a millennial — not a Boomer, so we can’t just attribute his stance to nostalgia for the music he grew up on, because he expresses admiration for music that pre-dates his generation. Still, I’m not sure how receptive the critical establishment will be to what Mohan and Beato are identifying. I imagine the current regime will find ways to deflect focus from Swift here, as usual, and pathologize Beato and Mohan as somehow overstepping their bounds.

It’s not the fanaticism of Swift’s fans that bothers me —people are welcome to like what they like, and if they feel moved on such a profound level by her music, then I (or anyone) would be wrong — dead wrong — to tell them they’re wrong. I actually enjoy listening to people talk about why they like the things they like — even when I don’t like those things. So much so that I can be engaged in an entire conversation with someone without ever letting-on that I myself am not a fan of whatever it is they’re raving about.

If I do bring up my own opinion, I’ll usually just gently say something like “so far their music hasn’t clicked for me” or “I’m more partial to this other album or [other work by the same artist].” I almost never start pushing or lobbying for my reasons for not liking whatever the person is talking about. That seems so… emotionally unintelligent to me, like doing a very poor job of reading the room. If someone is enthusiastic about something, to try and make an argument against that has always struck me as being in extremely poor taste.

If I’m good friends with someone, though, I must admit that I feel a lot more comfortable being an argumentative prick and shooting-down what they like, but even that’s rare, and it’s often done in a good-natured spirit of me and my friends just giving each other shit. A lot of the time, I’m making fun of myself as much as I am at the music in question, going so far over the top that the person who loves that music can take pleasure in laughing at me rather than take offense.

All of which is to say that I like to tread carefully around differences in individual taste. This most definitely carries over into my music journalism, where I do my best to be neutral. For my entire career, the one principle I’ve maintained with an unbudging militance — a fervor verging on fundamentalism — is that there can be no objective measure applied to art. I can make lots of points about music (or some other work of art) that you can relate to whether our tastes align or not.

I can’t tell you whether Taylor Swift(or anyone)’s music is or isn’t “good.“ In fact, I’ve done my best to excise the terms “good”, “bad”, “better”, and “best” from my vocabulary when discussing music. And I make it a point to never speak of one album or song by an artist being definitively “better” than another. The fact that this is common practice among music critics drives me up the wall. Frankly, I find it idiotic. Worse, it says to me that music criticism is, at its core, a kind of cognitive magic act, where the audience is somehow tricked into forgetting the most fundamentally axiomatic principle of music, which is that it’s all subjective.

Editors prefer to run lists with titles like The 10 Best Gardening Albums of All Time and The Chipmunks Discography, Ranked From Best to Worst (not real lists, but we can dream). I always balk at that terminology, but I play along when it’s not worth fighting over. My new ambient column, for example, is just way too fulfilling for me not to concede some ground. At the end of the day, the editors at PopMatters have to do what they can to drive traffic.

The people who run publications, alas, understand that the overwhelming majority of music fans who’d click on music-related links aren’t interested in letting go of their sense that music can be separated into “good” and “not good.” Judging from the preponderance of “Best” lists, these listeners feel that we should be quibbling over which music is “the best” or “better” than others. None of those people are looking for their balloon to be popped by a finger-wagging opinionist who invalidates their entire way of looking at music. (That’s what this newsletter is for!)

Most importantly: if the artists, their publicists, and their labels feel rewarded by having their release included on a “Best” list, then I’m more than happy to oblige them. But on the flipside, I do think it’s fair to push back on the notion of critical consensus — particularly when there’s a mis-alignment between what critics say about art and the art itself. For me, this discrepancy represents something more than just a gripe to chew on. I think it’s important to explore why this discrepancy exists.

If it was only Swift’s mega-popularity to contend with, I would have no issue with her success, nor would there be any reason to debate her artistic merits as I see them. Due to the decline of radio as a culture-defining force, I don’t think I’ve been subjected to even one of her songs against my will. I can’t think of a time I’ve walked into a supermarket or department store or diner or bar and heard her music playing. And, today, the media landscape is configured in such a way that we’re no longer bombarded by hit songs to the point where there’s no escape.

So I would most likely just pay little attention to her, and I’d leave it to the people who like her music to do their thing in peace. Aside from Swift’s stature as a commercial behemoth, she’s also a hard-working entertainer who found a way to parlay her unthreatening apple-pie persona into something like universal appeal. Sure, she and her team contrived her country-girl persona on false pretenses, but that wouldn’t matter to me if we simply viewed her as an embodiment of bubblegum pop. (For more on her calculated appropriation of country music, faking her accent, etc, I turn you over to the guys at Your Favorite Band Sucks:)

Swift’s authenticity only becomes a bone of contention for me in light of the way she’s framed. Tastemakers — particularly the highbrow, academic-minded ones at outlets like The New York Times, The New Yorker, Pitchfork, etc — continue to imbue her story with a political valence. Viewing Swift through their lens, she’s no longer simply a pop icon to be taken at face value, but a vessel for their broader observations about women’s sense of belonging in a world that still struggles to recognize women’s personhood in all its dimensions.

I can understand why it would be tempting to project a sense of moral victory onto one of the most successful and accomplished women on earth — well, I can understand it until I hear Swift’s lyrics. As social critic

has pointed out, one gets the sense of being gaslit by media figures contorting themselves in order to dignify Swift’s lyrics.Take this verse, quoted in New Yorker critic Amanda Petrusich’s review of Swift’s new album The Tortured Poets Department:

You smoked then ate seven bars of chocolate /

We declared Charlie Puth should be a bigger artist /

I scratch your head, you fall asleep /

like a tattooed golden retriever.

Or this one, also quoted in the same review:

You said I’m the love of your life /

about a million times /

You shit-talked me under the table /

talking rings and talking cradles.

Or take this line from “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” which features in Rick Beato’s video linked/embedded above:

I remember when we broke up the first time

Saying: "This is it, I've had enough"

'cause like, we hadn't seen each other in a month

All throughout Swift’s catalog, we see this same heavy-handed earnestness over and over. I find it difficult to reconcile her use of the word “poet” in her new album title, even if she didn’t mean it in reference to herself. And the more one combs through her songs, the more it becomes clear that Swift didn’t rise to the top of the mountain by exhibiting power as a woman, but by keeping herself stuck in a perpetual, arrested state of adolescence. She doesn’t paint a complex picture of desire, but an implosive one that collapses into a kind of cryogenically static naiveté. In her music, we never encounter desire or attachment that evolves beyond the bounds of unrequited crushes, puppy love, or self-pitying resentment.

This is not to disparage young people or demean their experience — we’ve all been there, and we all carry the wounds and need for connection of the young person we once were. There’s also a lot to be said about giving voice to the limerent form of preoccupation her songs so often touch on. But Swift doesn’t appear to have the tools to explore these kinds of feelings from anything resembling an adult perspective. And it’s hard for me to imagine anyone walking away from one her songs with a greater understanding of their own longing.

I have to wonder why this mode of expression has been so aggressively propagandized as something that it just isn’t. I mean, if you’re looking for a more convincing presentation of what being a young adult today feels and sounds like, just press play on the music of Olivia Rodrigo or Billie Eilish. They get plenty of coverage too, but there’s a stunted quality to Swift that I find disturbing given the fact that my peers — adults! — have in unison anointed her as an avatar. The dissonance between Swift’s notebook-scrawling juvenalia and the elocutions of a cultured wordsmith like Amanda Petrusich couldn’t be more glaring.

On first glance, Petrusich seems tailor-made to transmit and amplify the prejudices of people from the class background The New Yorker is written for. When she speaks, you can immediately tell she’s the product of a formal, high-level writing education. (FYI, her parents were public schoolteachers, and she didn’t start studying writing until college.) For me, the style and bearing of her writing voice echo back to an age when people who wrote for magazines used formal, professor-ly language. I actually wasn’t alive during the period I’m referring to. I’m not sure my mental image of this moment in the past is even accurate. But that’s what comes to mind when I read Petrusich — that there was a time when being an author conferred a certain intellectual weightiness draped in erudition.

For my money, Petrusich is a formidable writing presence whose natural ability just can’t be denied. Her phrasing, in fact, reminds me of the jazz musicians who’ve been armed to the teeth with musical training but still play with a soulfulness that suggests they’d have been just as compelling without the training. She’s also highly invested in what she writes about. Clearly, she cares — not just about music, but about its broader implications. (She also spoke eloquently with Anderson Cooper about her own mourning experience on Cooper’s All There Is podcast series in 2022.) There’s a kind of stalwart conscientiousness that permeates her work, and she has a way of disarming the musicians she speaks to with her down-to-earth manner.

In short, Petrusich is no dummy. (I don’t believe that “dumb” people exist, and I don’t believe that facility with language is an adequate reflection of the substance, value, or “intelligence” underlying what a person is trying to say. But let’s just agree that Petrusich makes sharp observations about the subjects she covers.) Which is why it stumps me that she wouldn’t recognize Taylor Swift’s lyrics more for what they are than for what she’s straining to see in them.

I’ve pushed back against Petrusich before — specifically her 2018 appearance on PBS NewsHour, where she called for music fans to engage in a kind of proactive, self-administered form of censorship that she insisted wasn’t censorship. I found her moralistic stance quite chilling. In the clip, she refers to “bad people,” as if any of us has the authority to determine who those people are. She also suggests that it’s “dangerous” to separate the art from the artist.

To be fair, the majority of my music-journalist peers would have wholeheartedly supported Petrusich’s stance back then, at least publicly. (Many of them still do, which I find reprehensible or, at the very least, supremely misguided.) What’s truly dangerous, as far as I’m concerned, is the idea that a small group of people can cash-in on moral panics as the basis for installing themselves as a Stasi-like secret police force, all in the name of serving as guardians of our conscience.

On discovering the NewsHour clip six months after the fact, I tweeted the following in response:

@amandapetrusich @PBS @NewsHour This clip is over 6 months old, but your premise raises some flags for me that I'd like to run by you…

I certainly appreciate the conundrum that "separating art from the artist" poses. I think this is a hugely important question every fan faces + I appreciate you bringing it up.

I'm also all about challenging the intentions behind an artist's work. But as a music journalist I'm uncomfortable w/ the idea that I'm in any position to decide who's a "bad person"

If you're challenging how we too passively look the other way when we like a song, I hear you. But I think audiences are reluctant to throw the baby out w/ the bathwater b/c they have an instinctual sense that people/life're complex

Any social issue requires nuanced examination + the good-person/bad-person model is a woefully inadequate measuring tool for dynamics that are baked into our day-to-day existence + require some mental gymnastics/rationalization to cope with

And I'm exremely uncomfortable with a cabal of critics leveraging their self-appointed position as the arbiters of taste into seizing the reins as our collective moral compass. Sounds like a power grab from people already drunk on power.

As I see it, our job as music journalists is to raise questions rather than impose answers. Like you point out, it's not easy to resolve when someone who's committed acts we find reprehensible also leaves behind something of profound beauty.

But if people have a hard enough time simply cutting off friends/family/loved ones when the same issue arises, how can we expect them to detach from music?

Also, aren't we in the music media double-dipping when we give these artists' music non-stop attention then wring our hands in dismay over their actions? Reminds me of sports commentators talking about the concussions in football.

I've been asking myself/wrestling w/ these same questions since I was 13 yrs old listening to #ReignInBlood. I trusted my own judgment then and I trust my judgment now so I like to address my audience as if they can trust theirs.

I couldn’t find the actual tweets themselves, but I cringed at the memory of having sent them. I had filed the memory away as if I’d shot-off an overly aggressive ten-tweet salvo, the kind that men all too often fail to realize lands poorly with women online. But on searching through old e-mails, I realized that I’d actually taken the time to try and come across as non-combatively as possible. (I still don’t recommend tweeting public figures in that manner, even when making a point one feels justified in making.)

Petrusich appeared on NewsHour at the height of #MeToo. But by then, many of my peers and editors, along with a raft of media outlets like Jezebel, Slate, The Daily Beast, etc — were already well down the road of promulgating a rigid new orthodoxy that they had successfully managed to brand under the umbrella of women’s empowerment. If you ask me (and other, more prominent, figures who publicly pushed back, like

, Laura Kipnis, Camille Paglia, etc), what was being sold to us as a new wave of feminism was in fact a regressive vision of women as helpless, dis-empowered beings who lack agency.Over the past decade, as concurrent social-justice trends have gained (and subsequently lost) traction in the culture, it struck me that these movements all revived regressive, sometimes centuries-old attitudes about the people on whose behalf the movements were being waged in the first place. On close inspection, for example, #MeToo revealed itself as a reversion to Victorian-era ideals about women’s purity. Pull on the thread just a little and you find that this conception of womanhood reeked of patriarchal values.

Similarly, much of the rhetoric infusing Black Lives Matter was rife with race essentialism. Meanwhile, the trans-rights movement ignited a culture war over definitions of gender, even though trans-rights dogma is rooted in self-contradictory essentialist assumptions about gender. If you’re seeing a pattern here, it’s because there is one: these belief systems have all flowed into our cultural groundwater from the top down, not from the bottom up. Which is to say that they’ve all trickled their way into mass adoption as the runoff of a privileged worldview.

So much of what passes for social conscience today reflects the unresolved anxieties, neuroses, and delusions of a white-American upper/middle-class demographic that would rather forcibly refashion the world in its own image than face its own demons. Not that people with less money and status don’t suffer from their own set of delusions, but (up until recently) it’s been clear which demographic has had its hands on the levers of culture.

In light of these broader currents, it’s time to probe further into the lionization of Taylor Swift. And — in an era where music journalists have made such a concerted effort to infantilize women and amplify their sense of helplessness under the pretense of empowerment — to take a closer look at their unwavering embrace of a performer who’s entire act consists of remaining frozen in girlhood, perpetually at the threshold of maturity but never quite there…

That said, if Petrusich’s review is any indication, we may may finally be at that point — among the review’s many nuanced criticisms, this one stood out to me most:

As I’ve grown older, I’ve mostly stopped thinking about art and commerce as being fundamentally at odds. But there are times when the rapaciousness of our current pop stars seems grasping and ugly. I’m not saying that pop music needs to be ideologically pure — it wouldn’t be much fun if it were — but maybe it’s time to cool it a little with the commercials? A couple of days before the album’s release, Swift unveiled a library-esque display at the Grove, a shopping mall in Los Angeles. It included several pages of typewritten lyrics on faux aged paper, arranged as though they had recently been tugged from the platen of a Smith Corona. (The word “talisman” was misspelled on one, to the delight of the haters.) The Spotify logo was featured prominently at the bottom of each page. Once again, I laughed. What is the point of all that money if it doesn’t buy you freedom from corporate branding? For a million reasons — her adoption of the “poet” persona; her already unprecedented streaming numbers — such an egregious display of sponsorship was worse than just incongruous. It was, as they say, cringe.

I may be reading too much into the The New Yorker’s willingness to take shots at Swift, but I wonder how much longer her grip on the chattering classes is going to last before the spell gets broken. Sooner or later, entertainment trends will take yet another turn towards more subversive, more unrestrained forms of expression. When I compare Swift’s appeal to the music young adults gravitated to in the ‘90s, the contrast is jarring.

Sure there were bubblegum mavens back then too — Britney Spears, Christina Aguillera, etc — but I wonder whether Swift’s popularity betrays the prevailing need for safety we see in young people today. Sooner or later, that’s going to shift. A new generation of kids is going to shatter the pieties of our time, as new generations always do. Art that revels in ugliness, that dares to pick at forbidden subjects and takes a jackhammer to the stultifying homogeneity of our current moment — it’s coming, like a train that’s still a ways down the track but headed our way nevertheless. If you crouch down and touch the rails, you can almost feel the vibrations on the rails, the rumbling clackety-clack carrying ever closer on the air…

When the train arrives and we turn that page, I wonder how future tastemakers will retroactively frame Taylor Swift’s story to fit whatever it is they want to see. Whatever happens, it’s going to be interesting to watch things unfold between now and then.

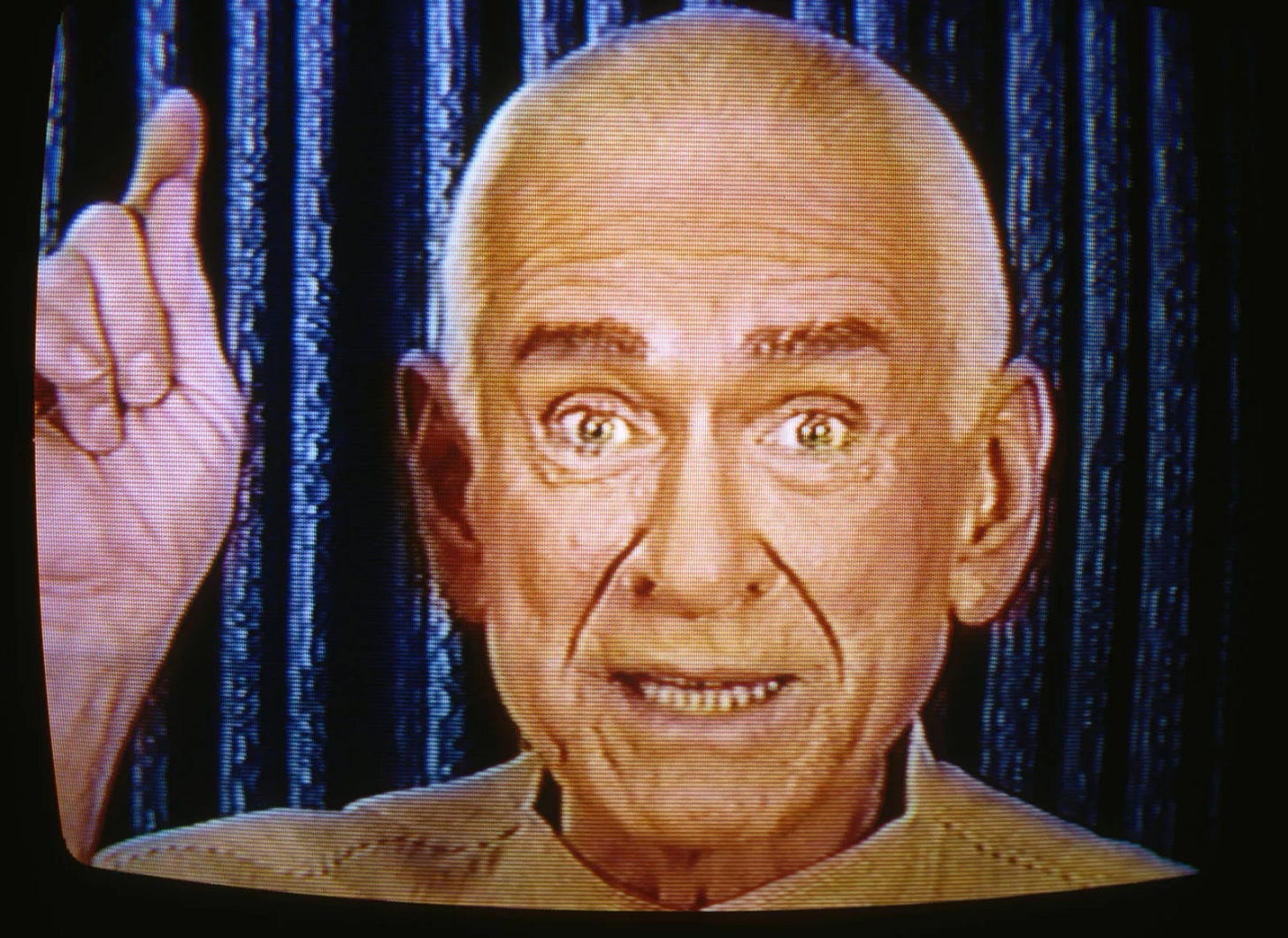

Here’s a great clip of the last two people who resisted joining the Taylor Swift cult:

😂😂😂

**update!**

Speaking of laugh emojis, immediately after posting this, I watched Darkness frontman Justin Hawkins’ YouTube breakdown of Taylor Swift’s 2022 song/video “Anti Hero.” Like Hawkins — stop the presses — I quite enjoyed the song and the video, both of which capture how Swift’s awkward, heart-on-sleeve disclosures can be relatable, and how the sense of vulnerability in her music can be endearing, even touching.

This YouTube comment from @polyester8844 sums it up best:

It's so crystal clear how this song's so personal and heartfelt that it could resonate with anyone who's struggling with occasional or frequent moments of self-loathe

I’ve long given myself the out that “ya never know, I may like her music down the line.” I change my mind on artists fairly regularly, sometimes after years of harboring a strong dislike for their work. I don’t think that’s likely here, though, because my general reaction to Swift’s music is one of lukewarm indifference — not the intense, visceral aversion that almost perfectly sets the stage for a sudden, unexpected change of heart.

About 30 years ago, I was sitting in my room one evening with my door open listening to Steely Dan’s Aja. I’d bought the CD, even though the music really bugged me. I mean, it really got under my skin. At that moment, my housemate at the time walked by in hall outside my room. I said something derisive to him about the music, and he stood in the doorway and said, “You know, you’re always talking shit about this album, but every time I see you, you’re listening to it.” At that moment, it clicked: that’s because I love it!

I’m usually not that fickle (and I don’t lose my taste for stuff nearly as much as I backtrack from my dislike of things), but I’m keenly aware that my receptivity is liable to change. Like I said, though, I don’t anticipate that happening here. I may see endearing qualities in a song like “Anti Hero,” but there’s still something about Swift’s energy that profoundly unsettles me. There’s an intensity in her eyes that doesn’t line up with the sweet, aww-shucks demeanor, and that raises my defenses — especially when I measure what I see in her eyes against the sheer thrall she inspires in her audience. Cult leaders have that look in their eyes too…

I forgot to mention above that on an episode of The New Yorker’s Critics at Large podcast from October of last year, Amanda Petrusich described being at a Taylor Swift concert and, in an arena full of people, having the uncanny feeling that Swift was speaking directly to her. On hearing this, my inner reflex to be on-guard awakened instantly, like a cat bending its entire spine when there’s danger.

I should point out that, although I think Swift comes across as slightly wooden and stiff, there’s clearly a charisma there. I can’t quite put my finger on where that charisma stems from — her brand, after all, is made of a kind of purposeful unremarkability. Unlike, say, Donald Trump or other figures who inflate themselves to larger-than-life size, Swift engages in a kind of constant self-downplaying, even as she pursues massive levels of attention.

But I can speak somewhat to what Petrusich was talking about, albeit on a much smaller scale: unbeknownst to me, Swift voiced the character of Audrey in the 2012 animated adaptation of The Lorax, a film I’ve absolutely loved watching with my daughter. And I have to say, there’s an intangible quality to Swift’s performance that I can hear in her voice alone — “magnetism” is maybe too strong of a word, but there’s something there. And if I picked up on it in that context, without even knowing it was her, I can only imagine what it must feel like for people who already feel a strong connection via her music.

And this is where I think we have a responsibility as fans — of music, film, sports, or anything — to take a hard look at the nature of fandom and what it does to the people at the center of all the attention we direct at them. Petrusich raises this same issue in her Tortured Poets review, when she asks:

How could anyone survive that sort of scrutiny and retain her humanity? Detaching from reality can be lethal for a pop star, particularly one known for her Everygirl candor.

I personally do not feel that the human psyche is built to withstand that much energetic input, which leaves us in a bind: none of us, myself included, is ready to give up on making people famous by enjoying the things we enjoy, nor should any of us refrain from striving for recognition for our own accomplishments. I do think, however, that as a society we’re capable of approaching fame from a different angle at the individual-user level by being more mindful of the psychic weight we put on the people whose work we love.

I’d suggest that the path to getting to a more balanced place is to start with separating the art from the artist in a whole new sense: by owning the love we feel as our responsibility, not theirs. We do this by making it a point to distinguish that our love is directed at the work, not the person. We are not, in fact, in a parasocial relationship with the artist, but with the art itself. The thing they create is your friend, your moral support, your shoulder to cry on, your companion that walks beside you through dark times, the voice that reminds you that you’re not alone.

This is a crucial distinction to make, and I would stress that it’s our obligation to start making it. If we start doing our part to understand that we put an enormous amount of pressure on people in the public eye, I think we can make a powerful shift in the nature of celebrity that will benefit everyone involved. The outsized expectations we have of famous people aren’t justified simply because we’ve paid to patronize their work.

The transactional exchange of money doesn’t grant us the right to de-humanize artists by projecting more adulation onto them than one person can reasonably handle. We need to be more evolved and empathetic with our entire model for recognizing and rewarding people’s accomplishments. The “rewards” often come with a price that’s far too steep for any one person to pay. It doesn’t matter how rich a person is are if they no longer have the ability to walk into a supermarket without being mobbed by people — a basic human right that the rest of us take for granted.

Regardless of where we might stand on Swift, then, she gives us all ample reason to clarify our relationships with art and the people who make it. After all, it’s not just the celebrities who’ve been get something in the bargain. We have too. And by simply asking What am I getting out of this? we’ll all be in a better position to separate what does and doesn’t serve us.

<3 SRK