The worst thing we can do for indigenous peoples is de-fang them and dumb-down their histories.

A call to restore our appreciation for complexity as our shared human trait, plus five of my articles that deal with conquest, subjugation, and displacement.

As I write this, the colors of the leaves in the western part of New York State are just starting to turn. Each day, brilliant shades of gold and red capture a little more of the ocean of green that will inevitably succumb to them. Around here, the beauty of autumn is nearly inescapable. Rochester, the city I’ve lived in for all of my adult life, is almost entirely blanketed by trees. Don’t get me wrong: this town’s flaws are legion and, in their own ways, also inescapable.

Much like its nearest metropolitan neighbors Syracuse and Buffalo, Rochester is still visibly haunted by the remnants of its Rust Belt past. The presence of hulking industrial ruins that sit there corroding and forlorn is so common they almost fail to register in your line of sight. And there are entire swaths of the city and surrounding suburbs that suffer from a particularly pronounced lifelessness, the cumulative result from more than fifty years’ worth of poor urban design.

Pictures of a vibrant, crowded downtown from the first half of the 20th century contrast starkly with the deserted hull that much of the city center feels like today. That said, Rochester has already bounced back from one major decline, having gone from boom to bust to boom once already. Of course, for the last 30 years, there’s been a creeping, inexorable slide into decline, though who’s to say we won’t bounce back yet again.

Enjoy my work? You can buy me a coffee — or donate via Venmo.

Subscribing to this newsletter also helps. Your support means everything, thank you!

For several reasons I won’t get into, I think Rochester is well situated to make a comeback. Regardless, the trees are still with us — lots of them, even in some of the more poverty- and crime-blighted neighborhoods. And even where the ugly scar of over-development has eaten away at the face of the region’s natural wonder like a flesh-eating virus, the natural wonder is still winning somehow. No matter how many soul-deadening plazas, parking lots, and housing tracts have popped up over time, we’ve only managed to put a dent into all the greenery.

It’s quite often that I marvel to myself and wonder how the people who first inhabited this area — the Seneca people — responded to its landscape in the time before it was ever developed. What kind of impact did it have on them (emotionally, I mean)? How often did they have moments where the sheer beauty of it all took their breath away as it does mine? Or were they forced to be so pragmatic about matters of survival that they didn’t think of the surrounding terrain as merely “beautiful” in the same removed, screen-like sense that we do.

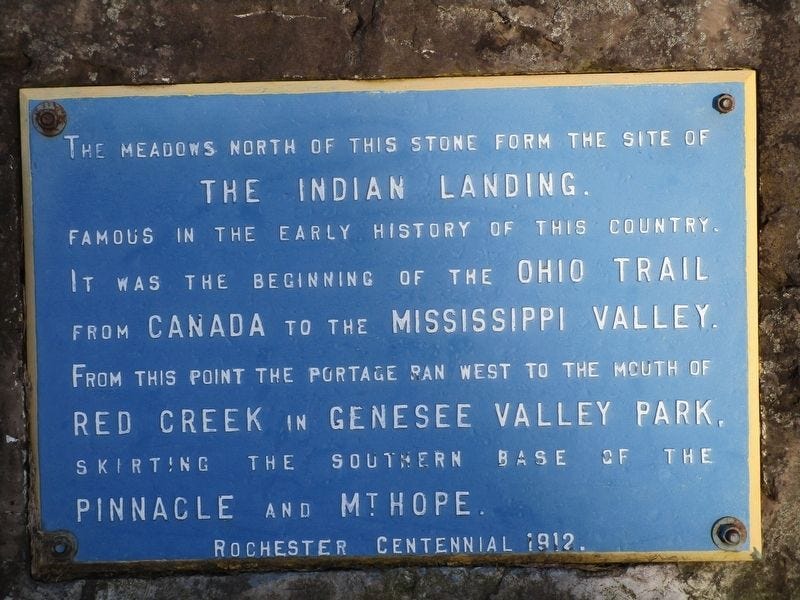

These questions have been popping up in my head a lot more these days. That’s because most of my mornings lately have started with a walk that culminates at a place with a spectacular view — a place, as it so happens, named Indian Landing.

I have to admit that I’ve studied very little of the Seneca and their way of life. For me, there would be something very sad about doing so, because it would feel like chasing phantoms. It’s also because I could swear their presence still hovers over us in some way — whether it’s literal or not, I can’t be certain. What I can say is that I often feel like I’m picking-up on some kind of residue that imbues all of us who live around here, in spite of how blind we remain to it.

I’ve often had the unmistakable sense that we need to face these phantoms, and that if we don’t, we’re only going to continue to drive ourselves into a collective psychosis that will eventually choke us from the inside out. And by “we,” I mean America as a whole — not just “white” Americans but all of us, including those who come here from elsewhere. Unfortunately, I only see us getting further from being able to do so.

Here’s the catch, though: from where we stand presently, it’s not the so-called racists or the oft-maligned spectre of “white supremacy” that are doing the most to keep us from getting there. On the contrary, it’s the people who’ve self-styled themselves as karmic debt collectors who, in my opinion, have degraded the conversation around race to the point where we’re rubbing our skin raw rather than applying the salve we so desperately need.

I won’t belabor my point, but I’ll just say that one of the most dangerous things we can do is to rob people of their complexity as human beings. When we do that, we refuse to see them. For the record, I have no opposition to the re-christening of Columbus Day as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Generally, I think it’s an important gesture for societies to recognize their indigenous populations — particularly populations that have been displaced or pushed to the brink of extinction. But in order for such a gesture to serve more than just a cosmetic purpose, it requires that we don’t make ourselves dumber in the process, and that we avoid the temptation to reduce people to noble-savage caricatures.

To mark the holiday, here are five of my pieces that deal with themes of conquest in different parts of the world — all of whose indigenous populations are worthy of being viewed through a complex lens, not as de-fanged paper-tiger decorations.

<3 SRK

Horror, mutilation, girl power, and the whitewashing of bloody conquest

I’ve often wondered how people through the ages have coped with the stress of raising children in perilous environments where natural hazards — like being mauled and eaten by wildlife — are part and parcel of everyday existence. I was reminded o…

Though set in the northern Great Plains, Prey takes place just as the Comanche were expanding into what we now refer to as the American Southwest. It’s a snapshot of a time before they adopted guns en route to becoming the most powerful — and feared — indigenous people in North American history. (Read more here, here, here, or here; listen here, here, and here.) Their path to conquest was notable for its violence, with the Comanche displacing and/or exterminating the Ute and the Apache but also establishing a robust trade infrastructure with Europeans while also holding ground against both the Spanish and the French.

As author Pekka Hämäläinen explains in his 2009 book The Comanche Empire: “The Comanche invasion of the southern plains was, quite simply, the longest and bloodiest conquering campaign the American West had witnessed.” Just to put this in perspective, Hämäläinen points out that the US-Mexico border was drawn where it was drawn — and Texas exists as we know it today — because of the Comanche’s dominance over the Southwest for the hundred-year period from 1750 to 1850. Hämäläinen describes them as “an extraordinarily adaptive people who aggressively embraced innovations, subjecting themselves to continuous self-reinvention.”

Or, as YouTuber James Hancock says in his Prey review, “[these were] not teddy bears [but] some of the baddest motherfuckers who ever lived.”

The indigenous settlers of a huge swath of North Africa ranging from Egypt all the way to the Canary Islands, Berbers collectively refer to themselves as Amazigh (pronounced ah-mah-ZEER) and speak an array of dialects of the Tamazight language. Their communities and customs tend to be interwoven with an Arabic presence and influence that dates back to when the Arabian/Muslim conquest of North Africa began in the 7th century. Today the Kabyle people continue to struggle against marginalization in a post-colonial Algerian society that’s dominated by Arab culture, language, and political rule—the central conflict that has defined Soula’s work and life story for nearly half a century. (Read full story.)

Of course, the de Jong brothers were born several generations removed from the scenes of violence and tragedy they describe in these songs, which don’t address the fact that, prior to the arrival of Europeans, Māori tribes didn’t identify as a single people and frequently engaged in warfare with one another. There’s also an argument to be made that New Zealand is actually setting an example for how societies around the world can begin to heal from—or at least acknowledge—the demons of their colonial past. (Read full story.)

“In the ’50s and ’60s — even the ’70s,” says Graham, “the Xavante were the most famous Indian group in Brazil. That has to do with the government of [longtime president] Getúlio Vargas, who was opening up the interior of Brazil to capitalist expansion. It was all part of his plan to conquer what he called the ‘hinterland’ and bring it under the control of the national society. It just so happened that that frontier expansion involved laying down a telegraph line across the country, opening up into the Amazon area and, basically, ‘conquering’ or ‘pacifying’ indigenous peoples — what the government called ‘contacting’ them — bringing them into the domain of the national society.” (Read full story.)

Against all odds, Die Antwoord became South Africa's most internationally visible pop export of the day by affecting a thuggish demeanor. Visser and Ninja are so precise in their ability to shift their weight between hostility, over-the-top hedonism and self-deprecation that they essentially parody the art of self-parody. Like hip-hop's answer to Larry David's TV version of himself, Die Antwoord is celebrated for saying things out loud that the rest of us wouldn't dare utter in public. With Blomkamp's film, in which they play themselves playing themselves playing themselves, the duo adds another layer to their satire. (Read full story.)