Artists: There's no need to ask people if they like your work.

When you create something, it's healthiest to see yourself not as a missionary but as a courier - a distinction that's crucial to your creative survival and overall well-being.

“If I ran a boot camp for artists…”

I’ve said those words out lout many times, mostly half-joking, but part of me thinks it would actually be a good thing if a place like that really existed — not the least because I myself would benefit from having a drill sergeant burst into my room every morning before dawn clanging a pipe against a garbage can lid while shouting GET YOUR ASS IN GEAR, GET OUTTA BED, DROP AND GIMME 20, AND THEN I WANNA SEE YOU AT THAT WORK STATION SHOWERED AND DRESSED IN 10 MINUTES FLAT!!! Then I would be able to say, in the immortal words of the late Hair Club For Men president Sy Sperling, that “not only am I the Artist Boot Camp founder, but I’m also a client.”

I mean, I could most definitely use help — even a forceful nudge here and there — when it comes to maintaining flow and staying on top of my routine. When I leave myself a blank canvas to picture what an actual training regimen for artists might look like, what comes to mind is a combination boot camp/retreat/motivational training workshop with a program led by people like Artist’s Way author Julia Cameron, Atomic Habits author James Clear (proponent of the “systems not goals” model), actor/real-life Marine drill sergeant R. Lee Ermey (of Full Metal Jacket fame), and buddhist monk Nick Keomahavong. There are probably dozens, if not hundreds of others whose work in the domains of creativity, routine-building, and mindfulness would bring a wealth of insight as well.

But when I imagine my original “boot camp for creatives” scenario, there’s a sign posted above every doorway that reads: As an artist, you are not a missionary — you’re a courier.

My basic-training setup is meant to be comical, but that’s only so that I can get this point across, which I’m 100% serious about:

We all want our creations to connect with an audience, but it’s not your job to convince people to like what you make. You are not seeking to convert anyone. Your job, though certainly difficult, is actually more direct and — in a way — simpler: once you’ve created something, all that’s left is to get your work in front of as many people as possible who have it in them to like it.

Again, “getting your work in front of as many people as possible” is not easy by any means, and that dimension of the creative life could keep any artist occupied until the day they die. Properly “marketing your product” and “building your brand” might even take everything out of you — but they won’t drain your life essence as long as you can remain steady enough to resist staking your self-worth on other people’s tastes. Their reactions to your work are completely arbitrary and don’t follow any consistent pattern. Thus, to put your sense of accomplishment in other people’s hands is to sign your life away.

But if you stand your ground, then you’ll have more energy to devote to spreading the word because you won’t have to burn a single calorie on trying to convince anyone that your work has value.

Of course, if this camp of mine were real, you’d see me huffin’ and puffin’ to keep up with the motivation drills. Lord knows, I don’t have the secret to staying in flow.

However, there’s an aspect of my make-believe “training” regimen that I believe in with every ounce of my being — so much so that I have to fight back the urge to bark the words at whoever will listen: Your job is not to get people to like your work. You’re not a missionary… On this I remain unequivocal, and it would be my wish to instill this principle in every other creative person I could ever convince. Not only would I love for each individual artist in my reach to strengthen their resolve to the point where it becomes unshakeable, but I would also like to see this idea spread so far and wide that it becomes axiomatic. I would love it if no artist ever asked the question “Do you like it?” ever again (other than small children, of course).

What I’m advocating for is a fundamental, radical — and yet strangely easy — attitude shift that can save your life. And you can yield the fruits of this adjustment instantly. When you cease viewing yourself as a solicitor and start viewing yourself as an instrument instead — as just a node in a chain or a spoke on a wheel — it gives you a better vantage point and better footing to hold yourself upright as you roll with all the turbulence that creativity inflicts on your system from within. After all, contending with the neurological challenges of being creative is difficult and debilitating and de-stabilizing enough on its own.

For me personally, being creative is like having a powerful, blinding beam of inspiration that’s constantly pointed at my brain. The beam then catalyzes more ideas than I can keep up with. I’ve often described it as an overflow of popcorn spilling out from my head at all times. The inner sense of pressure to “catch” those ideas — and the resultant guilt, shame, distress, discouragement, and dis-ease when I don’t — is enormous. No surprise, my relationship with my creativity requires constant maintenance in order for me to try and steer it to a healthy place. It has a times, been a toxic, utterly self-destructive relationship.

Imagine having an over-abundance of a precious substance (inspiration) and feeling like you’re squandering that substance. Imagine having something come so automatically to you that you often have to fight it back in order to concentrate on other things. My biggest hurdle — and the biggest threat to my work — isn’t what someone else thinks about something I’ve made once I’ve finished making it, which requires its own set of travails and emotional health risks in its own right.

Let’s not forget that once you complete the arduous journey from conception to finished creation, you’re sometimes left feeling depleted and out-of-sorts, kind of like someone coming down from a transcendent experience or, perhaps, an extended episode of mania. Finishing work can feel amazing and wonderful too, but either way, the neuro-chemical blast is so intense that it leaves the artist extremely vulnerable in its immediate aftermath.

To leave oneself open to outside criticism at that point is a kind of suicide.

From what I’ve gathered over the course of twenty-plus years working with artists, it’s all too common for creative people to be out of alignment with their own creative drive. So they don’t need to add this whole extra layer of what ultimately amounts to the self-imposition of conditional love — in a sense asking for others to gauge whether you’re worthy based on their response to the thing you created.

I couldn’t think of a more unhealthy and self-depriving pattern of behavior.

My recommendation is simple: Instead of asking “Did you like it?” you can ask “How did you feel?”

When I, for example, share something with people, I explain to them that I’m not looking for critique. My work is done, and whatever that person would do to change it isn’t my business any more than it’s my business if someone would prefer that my child had different hair or a nose that was shaped differently. I also say, “I’m not looking to know whether you liked it or not. Let’s imagine what I gave you was a film and you were part of a screening and I was sitting in the back row taking-in the audience’s emotional responses.” In other words, I’m curious about how it felt, but that’s not going to have any bearing on my direction.

When you adjust your angle this way, you can now function as a delivery system, rather than as a desperate, hungry beggar with your hand out for approval.

To better understand where I’m coming from, we can look at how the creative system works in reverse. Here it helps if you take a moment to think of an artist behind one of your favorite songs / albums / films / books / TV shows / etc — and I mean a work that you truly love. Surely, you're friends with someone who prefers different songs / albums / films / books / TV shows by that same artist and feels “meh” about the one that means so much to you. So now let's imagine that same artist in the middle of making that work that you love so much, and they turn to ask your friend for their opinion!

Well, if you're fortunate enough to 1) complete a series of works and 2) reach people with those works, then there are going to be people — just like you and the friend you thought of just now — who gravitate to different parts of your output.

Which is why your creative survival depends on being able to tune-out other people’s preferences — especially with regard to a work in progress (which is as fragile and needs to be handled with as much care as a premature baby), or a work you've just completed (in which case you’re in a fragile state and thus easily rattled by discouragement).

Of course we all want our work to connect with people! We would never share it with anyone if that didn’t matter to us. But detaching from how other people respond allows you the space to simply show up, receive the inspiration, convert that inspiration into art, and to repeat the process all over again. Because, let’s face it, you could just as easily find yourself frustrated — even disgusted — if lots of people liked your work but didn’t get where you were coming from. And where would that leave you?

I think I have an answer: Y’ever notice how squirmy, uncomfortable, and defensive some famous artists can be around people who truly, deeply love what that artist created? I would wager that artists don’t get prickly simply because they’re ungrateful or lack humility, or because they’re assholes. There’s a lot to pick apart in the dynamics between famous artists and their followers — too much to explore in a single-sitting format like this one — but I’m convinced that what I’m pointing to here plays into the equation.

I would imagine that people who’ve made the mistake of confusing other people’s love of their work for their own value as a person are in for a profound shock when they’re inundated with demand for that work and the demand doesn’t actually foster the sense of worthiness they were expecting. I would imagine it feels awful to achieve success on such a large scale and find yourself trapped, disillusioned, wanting, and dependent on others to feel good about yourself.

The good news is that the prescription for this problem starts with a simple decision that’s easy to stick to: get yourself out of the reflexive habit of asking the question “Did you like it?” whenever you show someone your work. If you just assume as your starting point that there are at least some people in the world who would like what you’ve made — if only they knew that your work existed — then you can resign yourself to the fact that it’s going to be a roll of the dice with each individual you come across. Some will like what you made and some won’t, so you don’t have to focus on those who don’t. You’ll never please them no matter how much you try.

Again, you’re a delivery system, nothing more. You receive inspiration, deliver that inspiration into tangible form (as in, like giving birth), and then deliver the finished artwork via whatever means of distribution you have at your disposal, in an attempt to reach every person on earth who might respond positively. Which means that, while you do need to put an enormous amount of elbow grease into hawking your wares, you don’t have to push the idea that your work has value. You already know it has value… at least to the people out there who would like it but have yet to discover it.

But Saby! What about collaborators, editors, producers, A&R reps, directors, acting coaches, agents, and anyone else who’s part of the process? Should we disregard them?

Hell no. I would actually prefer to work with an editor (with writing) and a producer (with music, preferably with other musician collaborators as well). I prefer working in a team creative setting. I think the friction and push-pull in those kinds of relationships is absolutely necessary for fueling the lifeblood of a project. I think having other hands in the pot helps both the artist and editor/producer/director get to places neither party would have arrived at on their own. I think true art is forged within a tangle of conflicting intentions — provided there’s some synergy there.

But when you’re working with other people, you’re walking side by side in a realm where outsiders have no place.

Around 2004 or so, I interviewed Los Lobos drummer Louie Perez, who described what it was like as the band embarked on the making of its enchanting, dreamlike 1992 classic Kiko, the first offering in an experimental streak that saw the band embracing risks: “It was like we [the band, producer Mitchell Froom and engineer Tchad Blake] were just peering out into the darkness.” In other words, they didn’t know where they were going to end up.

Perez’s choice of words really struck a chord with me because, in my own modest way, I’d been there. And the experiences were still fresh when I heard him say it: when I recorded bands at a studio in the town I live in from 1999-2001, I used to strongly discourage the musicians from inviting outsiders into our process.

“We’re out to sea,” I would tell them. “We’re the only ones who can find our way back to shore. No one else’s voice can help us out here because they’re not out on the same limb as us. We have to commit to finishing what we started before we start letting anyone else give us reason to second-guess ourselves — I don’t care if it’s your manager or your mom or your boyfriend or your best friend. You’re too easily discouraged at this stage, and it can kill your inspiration. You have to trust yourself.”

In other words: commit to the muse, goddamn it!

Chris Cornell once said that he didn’t want to feel like the bands he admired were thinking of him — the fan at home — when they made creative decisions. I completely understand what he meant.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum…

During one of the most memorable and rewarding recording sessions I ever got to lead, for the rock trio FMGreen’s full length debut Yellow #5 (which turns 20 this June), I witnessed first-hand what it looks like when a major artist does the exact opposite of what Cornell described.

As it turns out, all three members of FMGreen (who became dear friends of mine through this experience) were avid Weezer fans. In fact, if you squint hard enough, you’ll spot an FMGreen sticker on the guitar that Weezer bandleader Rivers Cuomo is holding on the cover of the second self-titled Weezer album from 2001, the one with the lime-green cover. And when we started work on Yellow #5 in January of 2002, Weezer happened to be right in the thick of what would become their follow-up offering, 2002’s Maladroit.

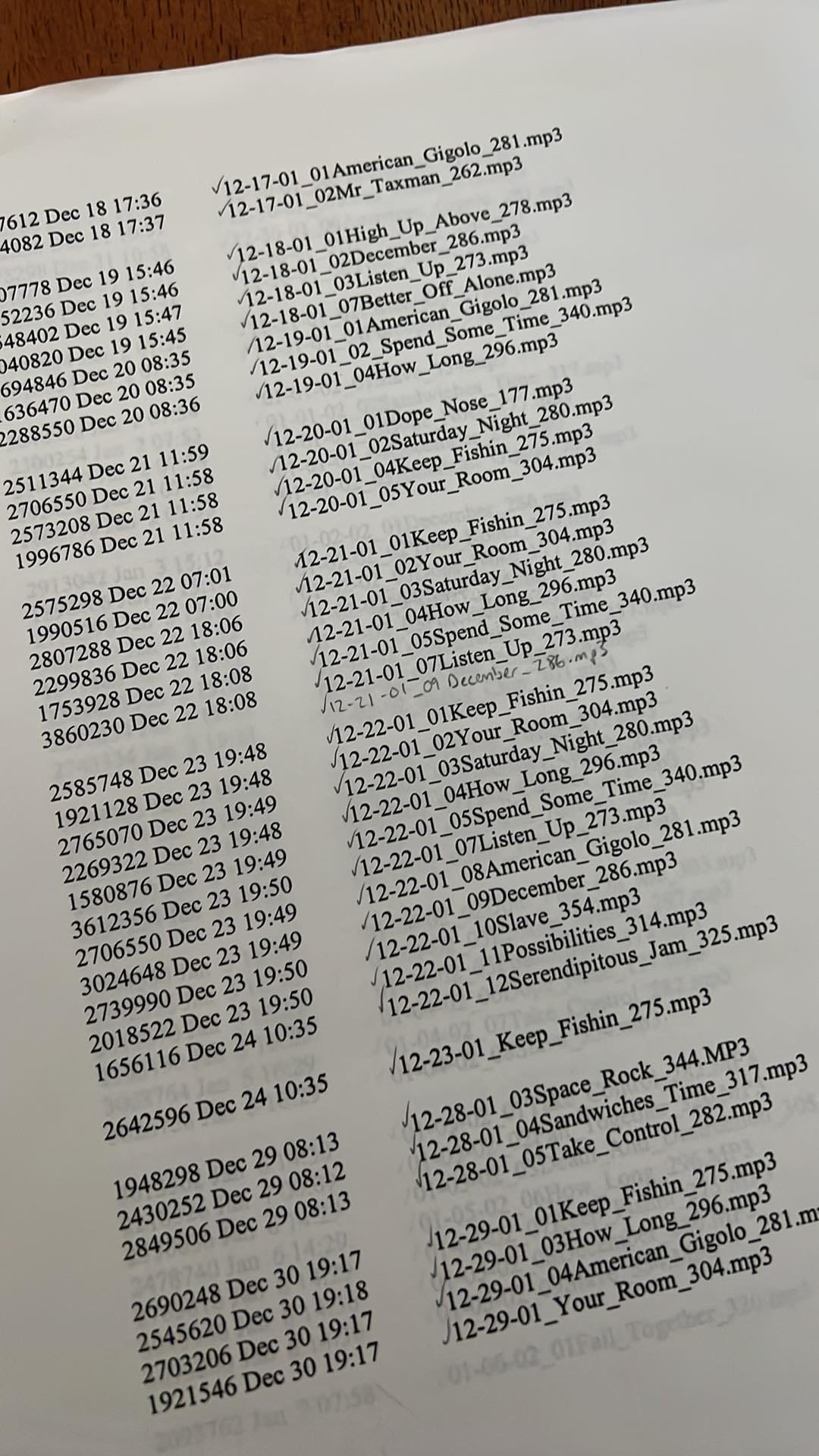

FMGreen guitarist Steve Lopez, an obsessive Weezer superfan at the time, would come to the studio with these meticulously organized laminated binders containing detailed, printed-out notes on the Maladroit material as it came together. I’ve teased Lopez about those binders for almost two decades, but the fact is they’re a shining example of precision, dedication, and documentation — the particular multi-media poetry of what fandom looked like in the early 2000s.

Sure, a lot of this info has been exhaustively catalogued elsewhere, but there’s just something about seeing it in print. And I can still picture the binders as the centerpiece of an exhibit at a popup Weezer museum, if such a thing existed.

I mean:

Here’s what you’re looking at: seizing on the then-emergent online infrastructure for connecting with fans, Cuomo set up a private message board where he allowed about 200 members to have an insider’s view of these songs as they evolved, sharing new iterations of the songs (now available directly from Cuomo) and soliciting feedback as he went along — a cardinal offense against the most sacred tenet at Saby’s Artist Boot Camp.

“Thanks for the help,” Cuomo wrote to one member. “I honestly prefer talking to people like yourself rather than a producer, a manager, or a record executive. You make suggestions motivated by artistic concerns, you posess a greater knowledge of weezer-music, and you notice the tiny details those other hired-hands miss.”

“I wish I could grasp the rock entirely on my own,” Cuomo continued, “but the truth is I, and most other musicians, need some sort of advising — whether it be from a manager, a girlfriend, or, in my case, an ex-fan, so… as long as you’re willing to give criticism, I’m willing to take it.”

My reaction:

In a message to someone else in the chat group, Cuomo wrote:

“What do you think about the fact that we don’t tune down half-a-step anymore? Good? Bad? No difference?

Boy, do I ever wish I could’ve given Cuomo a talking-to at my artist’s camp. It would not have been pretty. Admittedly, though, I enjoy the album Maladroit quite a bit, so it’s hard to argue with the results. Not to mention that I do feel a twinge of pride in knowing that Cuomo actually took Lopez’s suggestions for the guitar solo in the song “American Gigolo.”

And far be it for me to argue with a massively successful artist like Rivers Cuomo, right? Well… not so fast.

A quick re-cap of some pivotal moments in Cuomo’s career, which I’ve written about multiple times (like here, here, here, and here): within 15 months of its release, Weezer’s 1994 debut album sold two million copies in the U.S. (and is currently certified triple platinum, according to the RIAA Gold & Platinum Database). As any fan can pretty much tell you in their sleep at this point, the band’s sophomore follow-up, 1996’s Pinkerton, initially did a fraction of the business its predecessor did, taking almost five years to scratch its way to gold certification in July of 2001.

Selling 500,000 copies on the American market was nothing to sneeze at, even five years after the fact. Most musicians would kill to reach that level of sales even once. But on the heels of an out-the-gate blockbuster, Pinkerton was assessed as a commercial bomb. In a magical twist, though, the legend around the album grew over time, and by 2001 there was a cult of fans praising Pinkerton as an era-defining masterpiece. By all rights, Cuomo should have felt vindicated and triumphant, but he was never able to take the rejection in stride.

To make matters worse, Cuomo had laid himself bare with Pinkerton’s intensely personal subject matter. He’s never quite opened up to the same degree in his lyrics since then, and it took years for him to even acknowledge the album at all. If we read Pinkerton as Cuomo’s way of saying “here’s my heart for all to see,” the indifferent response clearly hurt him, leaving him hardened and wary of his fanbase. Several of Weezer’s subsequent albums have pointed 180 degrees in the opposite direction towards ultra-commercial pop.

Here’s what they sounded like just before pursuing that course:

Behind the gleaming, candy-coated exterior of Weezer’s poppy output, it’s as if there’s a real artist trapped in amber. There’s a cold distance and a withholding quality to that side of the band, as if Cuomo had grown cynical, resigning himself to playing the role of smiling organ-grinding monkey cranking out brightly colored but crassly commercial and, ultimately, lifeless music. I can’t actually fault Cuomo for taking this path — in fact, I think it’s genius that the band essentially alternates between two gears: “safe” and “weird.” Maladroit, for one, falls in the “weird” category, and the band sounds as alive, vital, and adventurous as ever, in spite of asking my friend Steve’s two cents on a guitar solo.

But I can’t help but think that Cuomo has made all of his career choices since 1996 as a reaction to a reaction — rather than just as an artist following his own path according to his own intuitive guidance, wherever that might lead. In a sense, Rivers Cuomo’s story is the perfect illustration of my point precisely because of his monumental achievements. The guy is a songwriting machine, capable of cranking out hit after hit. And yet he’s allowed so much of his expression to be defined by others. I mean, where is the confidence in that? What does “success” mean if you can’t break free of needing validation from your audience?

I just don’t think an artist — any artist, let alone an artist of that stature — should live like a prisoner. And so, if someone who’s sold tanker loads of records can’t make decisions from a place of trusting their inspiration, then we have to conclude that success doesn’t cure or compensate for that lack of trust. Which means that one needs to cultivate that trust in one’s own creative instincts right from the start — when there’s hardly any audience to speak of.

“Let’s get to where we’re going first,” I would always say to the bands I recorded, “and then you can invite all the outside input you want — when we’re done and you’re not able to backtrack or go around in circles, which you cannot afford to do while we’re still out to sea.”

The truth is, I would urge them to reject feedback when we were done too. My reasoning would go something like this: Let’s look at this finished work as a new lifeform you’ve just brought into being. You need to just sit with the sense of accomplishment for a while — reward yourself by luxuriating in it — before you invite the slings and arrows. I mean, why do this to yourself now?

I'm not saying you need to deny your desire for your work to be well-received. I'm saying that, once you put the requisite time and energy into your craft, you can train yourself to think that your work is going to be well-received by someone and gear your expectations accordingly. Which means you don't need to waste precious lifeforce pushing a rock uphill — you just need to find the hills where there’s already a built-in pulley system and the people at the top might even pull on the ropes with you to get that rock up to where they are.

Effective marketing shouldn’t be confused with currying approval on your new lifeform’s behalf, but should be viewed instead as properly outfitting that lifeform with wings (or maybe bright red plumage) so that it can go forth into the ecosystem. Whatever this creature does when it flies away and taps on someone else’s window is between that person and the work. It’s literally none of your business what kind of relationship someone forms with your creation. That aspect is no longer yours. The good news is that it’s also not yours to worry about.

But Saby! Are you saying that when I play gigs with my band we should just disregard the audience? Come on, reading the room is crucial. We’re not gonna just get up there and be indulgent if the audience isn’t feelin’ it. That would be like being a selfish lover who’s only interested in their own pleasure. Are you saying that artists should be selfish lovers? You can’t be serious!

Actually, I would agree with that. Live performance is something of a different animal than what I’m talking about, and I absolutely would not recommend being so hard-headed that you don’t take the audience into account. However, some of the same principles apply. Live audiences do tend to respond favorably to performers who demonstrate a sense of total conviction in what they’re doing. I, for one, have preferred to be sensitive to the vibe of the audience, but it’s definitely a two-way street, and if you come across as tentative and needy, it’s not going to work.

But wait! I cook in a restaurant — people have to like what I serve them.

Yes, but you would never stop carrying a certain type of hot sauce because some of your customers find it too spicy while others can’t get enough of it. Moreover, if someone sent a dish back, you wouldn’t invite the customer to stand in the kitchen and look over your shoulder while you made them something else. You wouldn’t stop every few moments, as you put this new dish together, and ask them if you were on the right track. Even a chef in that situation has to have the confidence to finish the job on their own. And at the end of the day, if the customer ends up asking for their money back or never returning to the restaurant, the chef has to live with the assurance that they’ve lived up to their own standards.

Moreover, people come to a restaurant because they’re craving a specific type of cuisine, so we’re not necessarily talking apples to apples. Linguist and social critic John McWhorter actually likens musical taste to knowledge of food, asserting that one needs to have their palette properly trained in order to appreciate music (specifically jazz), much as one needs to learn how to discern distinctions between fine wines. I beg to differ, but that’s a discussion for another day.

Hey Saby! I love getting critique because it helps me. All artists need critique, otherwise they’ll have no way of knowing whether their work is any “good.”

Oh, please.

I’ve taken writing classes where students comment on one another’s work. That can certainly be fruitful in that kind of setting. I’ve also led interviewing workshops where I play audio of interviews I’ve conducted and let the class have a field day picking apart my fuck-ups. It’s a lot of fun, and of course it’s fantastic to comment on each other’s styles — but in an encouraging way.

At a certain point, though, you have to pull the rip chord and trust that your own inspiration — and the elbow grease you put into bringing it to term — will work as the parachute.

I'm not recommending that you start your album of silky-fine electro/acoustic folk with a 17-minute track of pigs being slaughtered, or that you start your live set off with samples from that same track, blaring them over the P.A. at deafening volume when you’re opening for Lianne La Havas and Renata Zeiguer.

With your shrieking-pig loop safely set aside for the night, will you delight as members of the audience get swept away by your music? Will you walk away on cloud nine? Of course! But as you walk offstage and inevitably encounter someone who thinks that’s a good time to offer you tips on how to improve your act, remembering the words I am not a missionary… might come in handy. Feeling freed of having to convince anyone about your performance draws a protective circle that spares you aggravation, the reflex to defend yourself, or even being affected at all.

Not incidentally, the owner of the recording studio I mentioned earlier — Tony Gross, one-time guitarist of the classic rock band Head East and a personal mentor of mine — gave me the following sage advice one of the first times we went to scout a band at a gig: “Never criticize someone’s act right after they’re done playing,” he said. “You don’t want to deflate them in that moment.” I never forgot that. Unfortunately, not everyone you meet will have a Tony Gross on their shoulder. And you’re going to need a buffer.

I'm not suggesting that a restaurateur shouldn’t plan their inventory around customer demand — in fact, I think it’s a good idea to use platforms like this one to solicit questions from followers prior to sitting down with interview subjects. I think it would be great to have followers chime-in on my upcoming my book project.

But how the hell is that different than what Rivers Cuomo did?!??!

First of all, I don’t plan on outsourcing these decisions based on what other people like. I would open-up my process because I think it could be enriched by other people’s curiosity — not by their personal tastes. I’m not going to be sending drafts of my manuscript to a select audience and asking them what changes I should make. That’ll be the editor’s job. But brainstorming on what questions to ask interview subjects? I’m happy to approach that as a group effort.

My point here is that artists require a modicum of resolve and centered-ness in order to survive. You don’t have to be an absolutist, but any bending you do will prove much more rewarding if you anchor yourself first. Because getting lashed around by other people’s whims is not a healthy place to be. What I’m advocating is a transition from a state of grasping and never-enough’ness to a state of answering to the muse above all. In this state, you can feel lighter, no longer bogged-down by the extra weight of the one thing you have the least ability to control.

Imagine, moments after your child is born, going up to every person you can find, tugging on sleeves and insistently repeating, “Do you like my baby? Do you like my baby? Tell me what you would change about my baby.”

You would never do that — and it’s equally absurd to do that to your art.

In the popular fable The Miller, His Son and The Donkey, the two main characters take advice from everyone they pass on the road. Because they keep changing their approach, they end up dropping the donkey in the river, where it drowns — the perfect analogy for how staunchly one should guard the fruits of one’s inspiration from the interjections of passersby.

Being creative can put you in a position where you let what’s most precious to you fall away and drown because you’re too busy seeking outside input, but it doesn’t have to be that way.

And here’s the fun part: You won’t even necessarily know whether you like your own work — at least not from the perspective of someone in the audience. And that’s okay. You get to be in the audience for all the other artwork that exists. When it comes to your own stuff, all you have to do is show up, draw that circle around yourself (like salt that wards-off the noise of critiques), stand tall, and then…

Listen, receive… deliver.

Easier said than done, I know, but the alternative is way harder.

You might also enjoy…